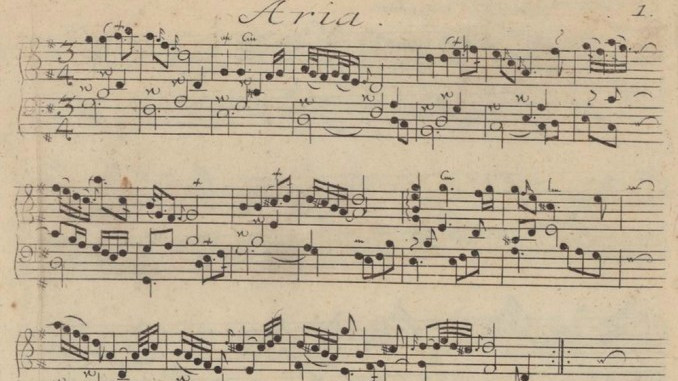

Gregorio Allegri composed the Miserere in 1638, but unlike most music of the time, which was performed and then forgotten, this piece continued to be produced long after the composer died. It is one of the most famous and iconic pieces of polyphonic music still—and frequently—sung today. The first extant source of the piece is from 1661—nine years after Allegri’s death.

Allegri was Maestro di Capella at the Church of Santo Spirito in Sassia and was part of the Papal choir of the Sistine Chapel until his death in 1652.

The style of the composition is called falsobordone, which is a form of musical recitation consisting of a basic note (or Psalm tone) with a cadence. The cadence can be more or less ornamented and was often improvised by the four or more voices that are required to sing it. Falsobordone, like the English equivalent faburden, most likely came from the practice of “cantare super librum”—meaning “singing over the book”—involving polyphonic improvisations and harmonies over a basic Psalm tone.

Miserere mei, Deus—Have Mercy on me, o God—are the first Latin words of Psalm 51, which choirs sung as part of the liturgy during Holy Week.

Allegri wrote this piece as two falsobordoni for two separate choirs (four and five voices, respectively) that alternate between the verses, having a monodic chant in between. Both choirs sing the final verse together.

It was only in 1771, over a century after its composition, that Miserere was printed and published for the first time. The legend goes that Pope Urban VIII himself decreed under pain of excommunication that the piece must never be copied outside of the Sistine Chapel. But when 14-year-old Mozart traveled to Rome and heard it performed in the Vatican chapel, he wrote it down from memory, whereupon it was published in London a year later.

Another composer who subsequently heard it in the Sistine Chapel was Felix Mendelssohn, and he, too, wrote down part of it from memory. The pitch in the Sistine Chapel at that period was a third higher than normal pitch. Therefore, what Mendelssohn heard and transcribed in 1831 was in a higher key than the performances of the Miserere that had preceded Mendelssohn’s time.

When a small section of this higher transcription was used by English musicologist W.S. Rockstro to illustrate an article in the first edition of Grove’s Dictionary of Music and Musicians, it so happened that the striking part of the change from G minor to C minor was introduced by accident. This led to the exquisite high C note that we hear in this piece, but that was never sung during Allegri’s time.

It may well be one of the most beautiful “errors” of musical history.

Related:

Miserere by Gregorio Allegri, Wikipedia

Celestial

Very beautiful piece of music.

Thank you for posting this. Just what I needed today. Can you please tell which choir is singing and which church this is being sung in.

Divine!

Thank you – exquisite.