“In opposition to the general pessimism, I set the search for joy, for pleasure.” René Magritte

By Nina Heyn, Your Culture Scout

The Belgian artist René Magritte made his name as a surrealist in the 1930’s, joining a cultural movement that has been spreading since 1920’s and already included poet Guillaume Apollinaire, who coined the very term “surrealism,” André Breton, the movement’s theorist and leader, and many artists such as Salvador Dali, Max Ernst or Louis Buñuel. Surrealism was upending the established rules of narration and imagery, and introduced into arts the notion that art does not necessarily has to be a representation of the visible world. A painting would have its own logic, often of a dream or an absurd thought, and it could be painted with all the precision and mastery of a landscape painter, but it did not have to represent any actual, “sober and sane” reality. This approach to art dovetailed perfectly with the new, non-Newtonian physics, the sense of absurdity of human condition brought over by the atrocities of the First World War and the birth of psychoanalysis, hypnosis and other explorations of the subconscious. Many of the seminal Magritte paintings were painted in the pre-war decade and made him one of the key representatives of this art style. Then the Second World War came, the classic surrealism was not so new and revolutionary anymore, and Magritte became a bit stuck. He was physically stuck in the wartime Belgium and he was artistically stuck as well.

A major exhibition at San Francisco Museum of Modern Art is exploring Magritte’s artistic development from precisely that point: his colorful “sunlit surrealism” and “vache” periods in the 1940’s and his exuberant explosion of creativity in the post-war years.

Around 1943 Magritte started painting canvases that had a palette of an Impressionist painting, even if they had some vaguely surrealist theme. A good example of this is The Fifth Season (La Cinquième Saison) – a painting that actually gave the title to the entire exhibition. This picture and the subsequent ones that he had been painting till 1947 belong to what has been called his “Renoir” period. Magritte was deliberately invoking Renoir’s colorful palette and a style of light strokes but the themes are his own: bowler-hatted men walking in opposite directions like a scene from a movie by his fellow surrealist Buñuel, or a portrait of a nude that would be a perfect Impressionist painting if not for the fact that each part of her body is in a different hue, from orange to blue. These are great, fun paintings that are rarely seen outside their home of Musées Royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique in Brussels.

Since neither his “sunlit surrealism” canvases nor his satirical paintings (called “vache”) have found much acclaim, in late 1940’s Magritte came back to his precise, clean style and cerebral creations. However, it was not a straight return to simple images of surrealist juxtapositions of pre-war art that was designed to “shock the bourgeois.”

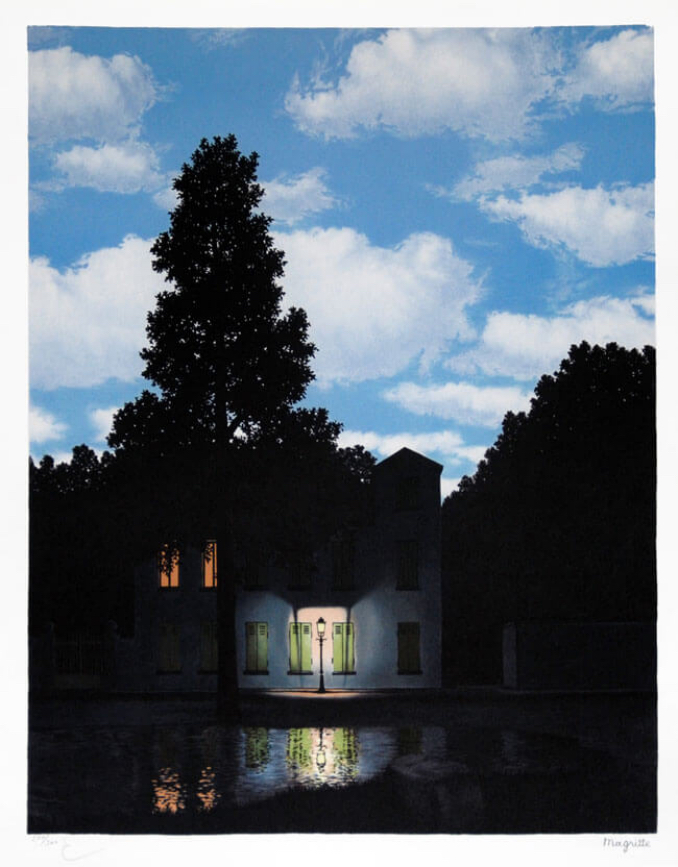

The SFMOMA exhibition is beautifully curated. It brings together paintings that are either not very well known in the US or would not have been seen together in one room even by Magritte himself. A case in point is a display that presents six different versions of his famous series The Dominion of Light (L’Empire de Lumière). The first one Magritte painted in 1949 and it was purchased by Nelson Rockefeller for his secretary. Another version ended up at New York’s MOMA. These days, probably the best version is in Belgium, another one is in Venice and another one is in Houston. Since they were painted over 15 years and sold to different locations, Magritte would never have a chance to see them together- but at this exhibition you can.

This is one of the most powerful and beautiful commentaries on what “light” means in art and what “time” means in physics. Each painting is a variation on a fairly simple image – a city townhouse, a street lantern in front of it, some trees, a sky above. What makes it surreal is the fact that we can see ALL times of day at the same time – the sky is a noontime blue with puffy clouds, the lantern is lit at dusk, the window is lamp-lit for the evening, the trees around it are dark shadows of a park in the middle of the night- all moments of time are present simultaneously. These are amazing paintings – beautifully rendered, full of deep existential thoughts and at the same time so emotionally satisfying. Over the years Magritte created 17 oil and 10 gouache versions of this theme. The fact that you could see several different versions of The Dominion of Light in one room is like Christmas come early present from SFMOMA.

The Dominion of Light series continued for many years – each time a bit more different – and it became one of his trademark images. Another one was the famous bowler hat. Magritte transformed his early “man-in-a-bowler-hat” images from placing an accidental person inside a composition to making it a symbol of a viewer to finally establishing it as his alter ego. The bowler hat appears in a total of 54 paintings, making this figure his artistic signature. The exhibition brings in many examples of how he used this image in various periods and compositions – all of it though-provoking and fun.

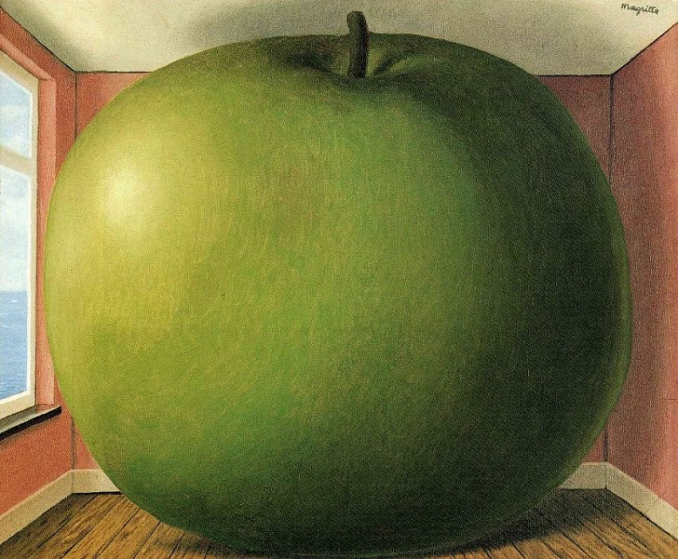

Another series of paintings so carefully assembled at the exhibition include examples of his “hypertrophic” i.e. overgrown objects – an apple, a rose or a rock that fill an entire room- clearly an impossibility unless you are an ant in a dollhouse but so pleasurable to consider. There are also his surrealist landscapes full of realistic rocks in unrealistic rooms or unrealistic eagle mountains against a realistic sky. Each of this paintings is more than a quick-look experience. You can go back to it many times, discover a different thought or a different texture, think of philosophical implications or artistic references. A mature, post-war Magritte was a master of both his brush and his ideas, all of it in such delightful juxtaposition of obvious and hidden, or realistic and disruptive. By 1950’s Jackson Pollock was in full swing with his splashy abstractions and Francis Bacon was creating his anguished human forms. Magritte stuck to his precise, almost naïve men in bowler hats and lush landscapes that look like something painted by Rousseau if he ever went to an art school. And yet… his art feels much fresher and satisfying than many art movements and experiments that followed his mid-century output.

Check It Out!

3rd Quarter 2018 Wrap Up: Megacities and the Growth of Global Real Estate Companies (102 pages)

3rd Quarter 2018 Wrap Up: Megacities and the Growth of Global Real Estate Companies (102 pages)