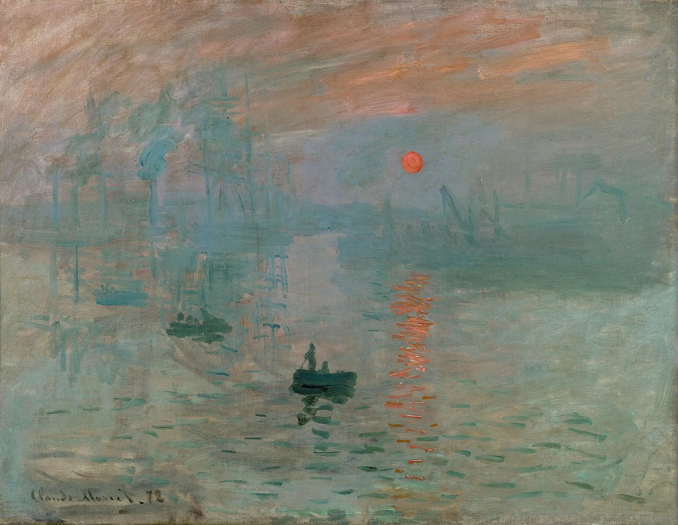

“Apart from painting and gardening, I’m good for nothing. My greatest masterpiece is my garden.” Claude Monet

By Nina Heyn, Your Culture Scout

It goes without saying that you can literally spend weeks in Paris just visiting museums, taking in sights and exploring points of interest and there will always be something new to discover. With less time on hand, it may be fun to do just a tour of all things Impressionist, or, even more specifically, take an in-depth look at one very prolific artist, Claude Monet. Monet is not only one of the key artists who came up with a radical new way of looking at and representing the world in paintings but he is also the one who is actually credited with “inventing Impressionism” since his seminal sunrise painting Impression, Sunrise was exhibited in 1874 to a sarcastic review mocking the new way of painting, the “impressionism.” Since his art is not only visually very accessible (who does not like pretty flower paintings?) and to great extent in public domain (and therefore gracing every coaster and tote bag imaginable), you may have been tired of looking at these images everywhere. It is however a refreshing way to spend a day in Paris museums just following Monet’s artistic ideas and his role as a bridge from the style he practically invented to the 20th century abstractionist art.

A tour of Monet’s heritage can start at the most comprehensive and popular destination for all Impressionist art – the Musée D’Orsay which houses masterpieces from mid-19th century all the way to the First World War. Since pictures are hung in chronologically arranged rooms, Monet’s landscapes are “competing” with masterpieces by his contemporaries: Renoir, Cezanne, Sisley, Dégas and Caillebotte, Gauguin and Van Gogh. It is however, a good place to start entering Monet’s world because some of his most significant paintings are displayed there: Argenteuil Bridge (1874), Poppies (1873), St. Lazare Station (1877), Haystacks (1891) and then a series of garden images from Giverny: Lily Pond (1899), The Artist Garden at Giverny (1900), Lily Pond, Harmony of Pinks (1900) and Blue Water Lilies (1916). Those ethereal compositions of pinks and violets can be our guide through a couple of more museums all the way to their incredible source.

The next stop is therefore Musée Marmottan Monet, a fairly small museum that houses a few major art collections, including about a hundred Monet paintings donated by several major collectors and Monet’s younger son Michel – making it the largest depository of Monet’s work in the world. Monet collection includes the artist’s letters, photos and souvenirs, as well as many artworks that he kept in his bedroom until his death – some of the best canvases by Renoir, Caillebotte and Cézanne. These are paintings that were kept in the family long after the bulk of Monet’s work dispersed into museums and hands of collectors around the world. Marmottan is also the place where you can find the very painting that started it all (i.e. Impressionism, Sunrise), as well as some examples of his other famous themes – Rouen cathedral, St. Lazare station – his own pictures that he prized so much he never parted from them. Some of the most amazing Monet’s canvases in this collection include his late, large scale works depicting flowers and plants that are no longer classic “impressionist” landscapes of his younger years. These have been painted well into the 20th century, when the artist moved towards a much more abstract style, while his palette got more muddled (perhaps because of failing eyesight) and some of the paintings look abstract and very modern in its application of color, unfinished edges and an expressionist, jagged style of lines.

Picture credit: Public Domain https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=23750619

Well into his 70’s, Monet embarked on a new project to which he devoted his entire energy and attention: creating 18 large panels that were arranged into semicircular strips of pond images called Nympheas (Water Lilies). He had a studio constructed to be able to paint these massive panels. He never exhibited or sold them, but he eventually offered them to the nation on condition that they will be displayed properly in a specially built space at Musée de L’Orangerie. He made this offer to his friend and the Prime Minister of France George Clemenceau the day after the First World War ended. These “grand decorations,” as Monet called them, got installed almost 10 years later in 1927 but by then the art taste has changed, and the canvases were deemed old-fashioned, spurned by both critics and the public. They came back in vogue in the 1950’s, and curiously enough, they made an impact on some American artists whose canvases were inspired precisely by these late Monet’s compositions of monumental plays of color. In fact, there is an exhibition right now at the L’Orangerie that draws attention to these American abstractionists whose paintings derive in some way from the artistic legacy of the Water Lilies – Jackson Pollock, Sam Francis, Joan Mitchell, Jean-Paul Riopelle, Helen Frankenthaler. Once the interest in those unusually shaped, monumental paintings was ignited in the 50’s, they have been a favorite destination for Paris visitors ever since.

It is really not possible to fully understand Monet’s art without visiting its source and its culmination. A house in Giverny, a picturesque village in Normandy about 75 km from Paris, was rented by Monet in 1883 and by 1890 he became its owner, free to dig a pond, divert waters of a nearby rivulet, and to plant thousands of flowers and greenery- all according to his vision and composition needs. He spent 43 years in that place, changing the pond three times, re-arranging flowerbeds, presiding over his extended family, receiving artists and politicians in his salon filled with his canvases and most of all – painting. Over and over, painting water lilies and chrysanthemums, willows and bluebells, always slightly different, always to serve his vision of how the colors should affect each other or what light does to a particular surface. He traveled to other places and painted other landscapes, cathedrals and seascapes, even portraits. But Giverny was his artistic touchstone, his safe harbor and a living canvas on which he painted for decades. To visit the Giverny garden is to step into his paintings and to literally touch the flowers that inspired so many of his canvases. The garden’s most famous feature is a large pond covered with pink water lilies that can be viewed from two green bridges. Next to the house there are flower beds spilling brightly colored varieties of seasonal flowers, and a central path is lined with trellises to support wisterias and hanging roses. Even if you are not that much into flowers and horticulture, the sheer orgy of spring or summer blooms is an experience of art in motion. The flower extravaganza even spills onto the neighboring village lanes (famous as an artist colony practically from Monet’s time) with ditches and fences covered in roses and poppies everywhere. The fun for a visitor at Giverny is to find a vantage point to recreate in a photo one of Monet’s paintings or simply to discover which painting was inspired by what area of the property.

There are various impressive gardens around the world – such as the orderly, enormous garden of the King Sun in Versailles where every square foot of vegetation is bordered and trimmed according to the exacting plans of the architect Le Nôtre and his successors, or its opposite in various English gardens created around castles in Great Britain, full of cascading rhododendrons and meadow flowers. The difference is that the Giverny garden was not planned by an architect or a gardener hired by a nature-loving owner of a nearby grand house. It was planned by an artist in full powers of his craft, to become a living tableau of nature and a flower arrangement on a grandest scale possible. Monet was able to spend decades at Giverny exclusively painting his water lilies and willows and always finding a new way to express something in art .

Check It Out!

3rd Quarter 2020 Wrap Up: Visions of Freedom (104 pages)

3rd Quarter 2020 Wrap Up: Visions of Freedom (104 pages)  Working Successfully with State Leaders Who Will Take Responsibility (20 pages)

Working Successfully with State Leaders Who Will Take Responsibility (20 pages)  Financial Transaction Freedom (14 pages)

Financial Transaction Freedom (14 pages)  3rd Quarter 2023 Wrap Up: The “AI Revolution”: The Final Coup d’Etat? (88 pages)

3rd Quarter 2023 Wrap Up: The “AI Revolution”: The Final Coup d’Etat? (88 pages)  2021 Annual Wrap Up: Sovereignty (232 pages)

2021 Annual Wrap Up: Sovereignty (232 pages)  Women in Art (254 pages)

Women in Art (254 pages)