If we look at a community as a financial ecosystem with financial sustainability as one of our goals in achieving overall sustainability, one of the questions we should ask as we reduce waste is “who gets the benefit of that waste reduction?”

In classic market language, if we improve efficiency, whose expenses go down or time is saved or risk is reduced and whose equity increases as a result? In every community, we have financial capital – whether investment dollars or philanthropic dollars – leaving the community for investment elsewhere or for investment in large enterprises that use it to come and buy up our communities.

Who and what will attract that capital back locally and do so in a manner that ensures the successful safety and performance on those dollars? And if it comes back to be invested locally, who gets what as a result? The more we can make our waste reduction attractive to existing local capital, the easier it will be to sequence progressively more waste reduction. The more we can make our local purchases interested in supporting the enterprises funded with our local capital, the easier it will be to generate the performance we need to affirm our local capital and to retain and attract the human capital that could make this all go.

So one measure of the success of a community-wide permaculture development should be an improvement in local investment performance as a result of progressive shifts in a portion of locally controlled and managed capital out of investment in large corporations (such as the financial stocks where they have been losing a great deal of money) back into the local investment system.

Creating this positive loop of attracting local investment capital and eventually regional investment capital is critical to the overall development. The usual alternative is to use government funding and some foundation and philanthropic grant making. These sources depend on borrowing (or capital gains which may be sourced from companies dependent on government contracts, purchases and subsidies which are dependent on borrowing) which is dependent on military force to sustain. Such funding brings those energetics and central controls to bear on a local development.

Sustainability calls for financial sustainability that is not dependent on centrally engineered funds but rather generates from tangible, value-added flows grounded in peaceful, free economies.

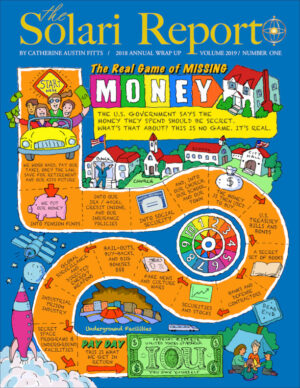

2018 Annual Wrap Up: The Real Game of Missing Money, Volume 1 (208 pages)

2018 Annual Wrap Up: The Real Game of Missing Money, Volume 1 (208 pages)

Last night, I listened to a fellow on web radio who had reduced his light bill in the Ozarks to about 20% of what it had been.

The other day He said He got notice that the electric utility company now wants to raise rates because electric use is down. If this is the reward one gets when he does what should be the right thing, how many are going to follow in the same footsteps?

I guess the next step is to unplug and self produce your power from the sun, wind, or ethanol (*) as needed.

(*) Hot water too

Catherine: I’m a permaculture designer who has thought of a new way to put bright, permie-trained young people inhabiting their “own” land through “tenured employment contracts” that require a percentage of production of their specialty, such as orchard/woodlot/bees, herbs, vegetables/grains, goat dairy, aquaculture(fish),value-added food processing, etc. for the thus-landed community and its mission (ie.organic restaurant, education or wellness center,small business incubator) A percentage of production would be the consideration for the contract securing permanent land tenure for the grower, (akin to the “publish or perish” requirement for tenured university faculty). Here tenure would also be secured for heirs or assigns so long as they produce,and their own surplus could be sold privately. Land title would be held by a foundation land trust whose covenants require the sharing of any profits from mission services (efficiency and equity gained) into local supportive infrastructures and equipment or further investments into similar landed permaculture system specialists, these working in concert under a wholistic design of the land and its productive systems. It takes 80% labor and capital to get permaculture systems up,(and time) but then only 20% to maintain them. This means very high efficiencies. Who gets what as a result? The growers get secure access to land rent free, healthy fresh food at no dollar cost, permanent semi-autonomous employment, the opportunity to share their knowledge and skill through apprenticeships, and institutional support for such things as group health insurance and the like. The surrounding community gets sustainable food-production facilities mushrooming all around them. Plus the mission services each land center will provide at low cost once up and running. In addition land restoration, soil building, water and carbon sequestration, low-cost natural building examples and standards, are primary within good permaculture design, and would be both land-healing and culture-creative in the local area. Of course loopholes around restrictive building codes would have to be researched and applied, but there are quite a few of those right here in over-regulated California. Farm Board and Forestry subsidies and grants could be researched and applied for as long as they are available. Once wealthy landholders see examples of this and realize how cheaply they could get educated “landed staff” producing all the custom-grown foods they could want (along with their own resident herbalist), they might try to hoard the efficiencies and equites gained from the specialized knowledge and willing labor of land-hungry people. However, if there were enough examples of land run under the permaculture ethics of land care, people care and fair share, it would be hard to attract applicants to a more feudal system.

Bravo! Well put.

Cathryn,

Your point was succintly made, when you talked about investing in your own communities for your own good. Borrowing money or depending upon the government is never a good thing. We have to be “creators” of our own wealth and of our own future. This does not mean, not working with the government, but taking more repsonsibility for our own financial education. So often we do what our parents did or we do what we have seen others do. Our actions have to be calculated and well thought through, if we are going to have financially sustanible communities.