by Catherine Austin Fitts

A very smart subscriber persuaded me to get this fascinating book in 2011 when it was first published. It has been sitting in the piles that have grown to several hundred books designated “Would Love to Read.” Our theme for the 1st Quarter Wrap Up is Planet Debt. So I dug it out and read it this weekend.

The author, David Graeber, is an anthropologist and professor at the London School of Economics (having been booted out of Yale). For me, reading anthropology is tough going. However, Graeber has worked hard to determine the facts of how a wide selection of the human race has managed to implement commerce and trade. Like all things human, the facts are different – and much more quirky – that we have been led to believe.

Most financial systems started with virtual currency – in essence with credit – rather than barter. Coinage has been much more a creation of the state, as were markets. The effort to herd the human race into financial systems that could be centrally standardized, controlled and managed has taken quite some time and a great deal of violence.

The anthropological view of how trade occurs “in the wild” underscores why Mr. Global is so enthralled with the possibilities of digital systems run through smart phones. Humans can return to our quirky ways with virtual currencies and Mr. Global can have a real time digital footprint of everything that can be managed with artificial intelligence behind a “one way mirror” and the ability to herd us with entrainment technology and subliminal programming in the ultimate insider trading machine. More control, less overt violence.

Working my way through the first eleven chapters was the background for arriving at the best part of the book – the last chapter. Chapters 8-11 provide a tour of history: The Axial Age (800 BC-600AD); The Middle Ages (600AD-1450AD) and Age of the Great Capitalist Empires (1450-1971). The title of the last chapter, Chapter 12, is in a parenthesis – (1971 – The Beginning of Something Yet to be Determined).

Nixon taking us off the gold standard and the return to virtual currency in 1971 marks the dawn of a new era – we just don’t know what it is yet. Hence Graeber gives it no name, a start date and no ending date. We are in the next period and Chapter 12 is Graeber’s invitation to invent something superior to our current circumstance.

There are numerous points that Graeber makes in his last chapter worth emphasizing. In Graeber’s words:

“Reality, then, has become so odd that it’s hard to guess which elements of grand mythic fantasies are really fantasy, and which are true….One element, however, tends to go flagrantly missing in even the most vivid conspiracy theories about the banking system, let alone in official accounts; that is, the role of war and military power. There’s a reason why the wizard has just a strange capacity to create money out of nothing. Behind him, there’s a man with a gun.”

In the end Graeber comes down to what I describe as the “central banking-warfare model,” pointing out the extraordinary symmetry between the growth of US debt and growth of US military expenditures. He also points out who is financing some of it – “…since Nixon’s time, the most significant overseas buyers of U.S. treasury bonds have tended to be banks in countries that were effectively under U.S. military occupation.” He also points out the extent to which the “debt imperialism” of the US and IMF is becoming strained. Certainly, recent events such as the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank indicate that alternatives are growing. Graeber emphasizes the potential of the Chinese to shift the balance of power.

“One can see the great crash of 2008 in the same light – as the outcome of years of political tussles between creditors and debtors, rich and poor. True, on a certain level, it was exactly what is seemed to be: a scam, an incredibly sophisticated Ponzi scheme designed to collapse in the full knowledge that the perpetrators should be able to force the victims to bail them out. On another level it could be seen as a culmination of a battle over the very definition of money and credit.”

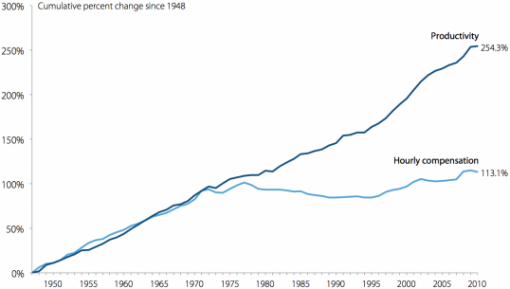

One of the things that Graeber addresses which is critical to understanding what is happening with debt is the abrogation of the tacit Post WWII agreement with labor – to share productivity gains with labor through higher wages. Indeed, I believe that this sharing only happened as part of a package to persuade labor and households to shift all of their savings into institutional control – including pension funds – providing a highly centralized control of an enormous cash flow. People thought these funds were their money. The events of 2008 provide that the system considered them their own – and the system could take them and replace them with fraudulent securities and debased dollars.

Graeber shows the shift in the allocation of productivity after 1971 – it all went to shareholders and investors. Labor got nothing. It is an ugly picture. When you look at corporations straining this year for profit to keep the equity markets strong, appreciate what has been extracted to date to get them as high as they are – and the devastating price that has been paid whether in stagnating household earnings or wasteful and illegal federal spending and credit.

Graeber points out the shocking divergence in the cost of capital to the rich vs. the poor. He describes the elimination of usury laws by Congress in 1980, making loan sharking legitimate as the wage squeeze shown above goes into effect. He described “a double theology, one for creditors, another for debtors.” Creditors are honored as they issue fraudulent securities and engage in predatory practices. Debtors are the new low class scum. Graebar quotes Margaret Atwood, “Debt is the new fat.”

“In the wake of the subprime collapse, the US government was forced to decide who really gets to make money out of nothing: the financiers, or ordinary citizens. The results were predictable. Financiers were “bailed out with taxpayer money” – which basically means that their imaginary money were treated as if it were real. Mortgage holders were, overwhelmingly, left to the tender mercies of the courts, under a bankruptcy law that Congress had a year before (rather suspiciously presciently, one might add) made far more exacting against debtors. Nothing was altered. All major decisions where postponed. The Great conversation that many were expecting never happened.”

Graeber then dives into the fact that growth can not continue – I disagree. Our environmental footprint needs to shrink and shift into alignment with our geophysical reality. It is possible to do that while continuing to build intellectual capital and financial wealth. What we need is a new economic model that aligns living wealth and financial wealth. As long as we stay in an economic model with a win-lose relationship, we convince ourselves that financial growth is bad. It is because it serves centralization instead of life. But that is an assumption – not a fait accompli. This realignment of life and finance is at the core of what needs to be reinvented.

Graeber goes on, “My own suspicion is that we are looking at the final effects of the militarization of American capitalism itself. In fact, it could well be said that the last thirty years have seen the construction of a vast bureaucratic apparatus for creation and maintenance of hopelessness, a giant machine designed, first and foremost, to destroy any sense of possible futures.”

Graeber has hit the nail on the head – management of popular opinion and surveillance and micromanagement of the population has reached a level that is so intense – and yet is so invisible behind the “one way mirror” that the average person can not fathom it is happening. He proceeds to discuss how we breakout of our current predicament to shift towards a more positive futures, pointing out that one of our challenges is that “the legacy of violence has twisted everything around us. War, conquest, and slavery not only played the central role in converting human economies into market ones; there is literally no institution in our society that has not been to some degree affected.”

Our challenge in envisioning freedom is that we have forgotten what human freedom is – what it feels like, what it looks like.

“If this book has shown anything, it’s exactly how much violence it has taken, over the course of human history, to bring us to a situation where it’s even possible to imagine that that’s what life is really about.”

The central banking-warfare model is coming up against it’s limits. Graeber see this. We all see this. It’s obvious. What he does not address are some of the great mysteries – why is the leadership so afraid and what are they afraid of? Where is all the money going? What do the real financial statements look like? Why do we all pretend the visible and invisible violence we are coping with in our daily lives is not happening?

One of the challenges we face with the current, continuing growth of global debt, is that it is hard to take it seriously. If the largest banks can issue trillions of dollars of fraudulent debt, have it refinanced by the taxpayers and continue to receive rich bonuses, then the whole thing is not serious anyway. It is not a financial system. It is a slavery system. And the only important question is who has a gun and who does not.

Graeber does not touch on gun control – even though it is germane to what comes next.