“Life is infinitely stranger than anything which the mind of man could invent. We would not dare to conceive the things which are really mere commonplaces of existence. If we could fly out of that window hand in hand, hover over this great city, gently remove the roofs, and peep in at the queer things which are going on, the strange coincidences, the plannings, the cross-purposes, the wonderful chains of events, working through generations, and leading to the most outre results, it would make all fiction with its conventionalities and foreseen conclusions most stale and unprofitable.”

~ Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, The Complete Adventures of Sherlock Holmes

By Catherine Austin Fitts

This week, attorney Carolyn Betts joins me to discuss Special Purpose Acquisition Companies (SPACs).

SPACs are essentially blind pools. Investors finance a company that has no business but is planning on acquiring another business. Among other things, this is a way for a private company to go public faster and do so with less regulatory scrutiny.

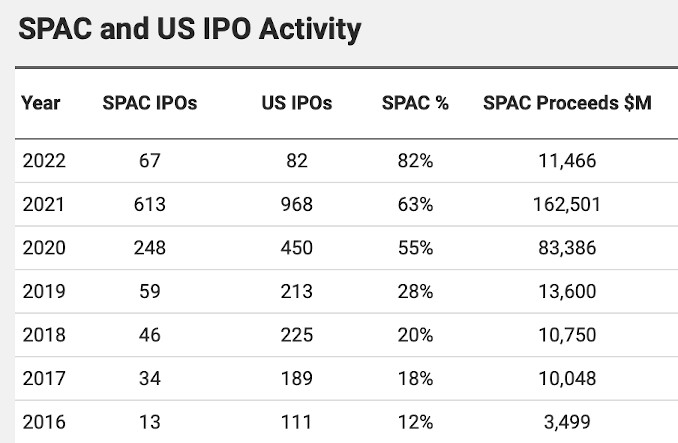

SPACs have traditionally represented a small portion of the United States initial public offering (IPO) market. However, after the G7 central bankers voted for the Going Direct Reset in August 2019, the volume of SPACs skyrocketed.

Source: SPAC Analytics

What happened and why? There are more than a few mysteries surrounding the explosive amount of money pouring into blind pools while the balance sheets of the Federal Reserve and global central banks were exploding and the small business sector was shut down or bankrupted. Are SPACs an investment craze fueled by central banker largesse, or a Going Direct laundry designed to target capital to specific investment teams and industries?

Think there is no money? Join us for our discussion of the financial tsunami that has poured into SPACs—a once-in-a-lifetime investment phenomenon that many of us missed while distracted by lockdowns.

In Money & Markets next week, John Titus and I will cover the latest events and continue to discuss the financial and geopolitical trends we are tracking in 2022. Post your questions for Ask Catherine or post at the Money & Markets commentary here.

Talk to you Thursday!

This looks to me as a private equity takeover transaction but skipping the holding part and taking it right away public, pocketing in the hefty fees arising from the SPAC set-up and management and skipping the IPO headache (and squeezing investment banks out at the same occasion). To sum it up, another way for Financiers to make money fast and “easy”.

I need to watch this a few times as I’m not familiar with SPACs, but I enjoyed this interview. Carolyn, you have a very easy way of explaining what seems complicated (and is complicated). Good on the CHD shows as well. Thanks.

Who are the auditors. Can’t read the tiny text on phone

It depends upon what years you are looking at, but the two that “came out of nowhere” (i.e., not big three or well-known regional CPA firms) with the most deals are Marcum LLP (and there’s a Marcum Bernstein further down on the list, which we speculate is an affiliate) and WithumSmith+Brown.

I really loved watching this video. Thank you for deep diving this topic. Because my experience with SPACS has been shall we say “less than fruitful” I am suspect of its nature. The one thing I got out of this video is that there is some pause as to how and why these things are financed. Something is going on in the background not yet identified. It’s too big a coincidence.

I’d be interested in a followup as to how each of these companies are doing and their current value on the market. I may do that myself if you have listed all 1300 companies. Are these companies a blight? Who knows? These companies it almost seems were thrown at us without too much due diligence. What are they up to now?!

Dennis:

The De-SPAC table has only the 300 or so companies that have gone through a business combination with a target. The full 1,300 SPAC table includes those that never combined and those that are looking or haven’t combined yet. Between the two tables you should be able to find both the SPAC symbol (as well as the warrant symbol) and the combined company symbol as well as a lot of other information. I’m skeptical of the rate of return information in those tales because I think there no positive RORs. The SPAC Analytics site has publicly available information on their calculation of the best performers. It’s really difficult to figure out a ROR because you have to consider the warrants and go though two or three separate entities (three because sometimes they form a third entity to roll up all of the SPAC and target shareholders into a new company). The Harvard articles are pretty good in looking at effects of dilution and pinpointing who is making the money on the SPAC process. Of course, we don’t know what the ROR is for the target shareholders or the PIPE and other private offering investors.

Thank you for a fascinating report. I especially like that the data you present in the tables can be sorted according to different criteria. I am looking forward to the written version so I can look in to this in more depth.

2 questions:

Are SPACs issued only in the US or are they also issued in other countries?

Hedge funds, for example, are available only to individuals with a certain net worth. Are there any similar restrictions for SPAC investors?

Andrew, I’m assuming they are an American phenomenon because they are structured to get around some of the more onerous or time-consuming issues with IPOs under the securities laws of the US, but I have not attempted to confirm this. A number of the SPACs are organized offshore (e.g., in the Cayman Islands or Isle of Mann) where they intend to acquire a foreign target. GRAB (a SPAC target) was an Asian company operating in Vietnam, e.g. All of the SPACs I looked at in our databases were listed on the NYSE or NASDAQ. It may be that they could be listed OTC. They’re all trading in the US. As for restrictions on ownership, no, the whole point is that the SPAC is offered pubicly, which means they can be bought on an exchange or OTC. It’s only private offerings that have investor qualification requirements. You would buy a SPAC, if you wanted to (they sure are long term investments unless you plan to redeem), in large part due to the dilution) through a regular stock broker (a persona now called a “wealth manager”!). All that I’m aware of are offered at $10/unit (share + fraction of a warrant).

Thank you, Carolyn, for your impressively comprehensive and comprehensible answer.

Usually large infrastructure projects involve the issuance of bonds and if done at the public level they also have a proposition to be voted on by the citizenry. I have not been aware of any such proposition having been held for the 5G network and all the towers that are going up. I have not heard about any bond issues or large syndicated loans for their financing either so I presumed that the financing was being done by private companies rather than by the government. Nevertheless I was left wondering how these private companies were going to finance such a huge project. Surely not out of retained earnings. After watching your report I now suspect that this is where SPACs come in.

Good question whether there are any SPACs in countries other than the US. A number of US SPACs involve going-public of foreign formerly-private companies where the final combined company is listed on a US exchange. When that happens, I take it that the common theme is the creation of a non-US entity (in Isle of Mann or Bahamas, e.g.) as part of a reverse merger transaction, or something like that. I have not looked closely at all of the offering documents so I’m basing my impressions on limited information as to the legal mechanics. I suspect SPACs themselves are a US phenomenon because they are structured around US securities laws, which are very different from those in, e.g. UK and other parts of Europe.

As for your second question, investments not open to the public generally are that because they are private issues, as opposed to public offerings registered with SEC. Private offerings use exemptions from SEC registration that usually limit investment to accredited (wealthy) investors. SPACs are public offerings registered with the SEC, so they are offered on exchanges and to the public without restriction except to the extent that the brokers must make sure the investment is suitable for the customer.

The aspects of the SPAC process that involve PIPEs and other private offerings of debt, convertible and/or preferred shares are private offerings, open only to accredited investors — usually institutions. Our PIPE investor data shows that mutual funds like Fidelity and Franklin Templeton and asset managers like BlackRock are the big participants in the private aspects of the SPAC deals. This may result in dilution to the public SPAC investors if the private investors negotiate more favorable pricing than the SPAC investors get. Once the business combination with the SPAC target company is achieved, the shares of the combined company can be purchased publicly, usually on an exchange.

I have invested in several SPACS and even more pre-IPO’s. I sold all my SPACS. They are a scam in my opinion. You end up investing in a company that you know nothing about. You are not privy to all the financial exponential increases that may be there for pre-ipo’s. Every SPAC price that I have invested in, went down once it split. And I mean to 1/3 its level. I sold everyone at a loss. Why the SEC puts up with it I will never know. It’s just a way to skirt SEC rules and regulations. Bad investment, don’t do it!

Thanks for that feedback. The reported rates of return that we’ve seen are not good.

SPAC’s are treated ( tax size and such) just as any other IPO?

I’m not a tax attorney, so my statements are based only upon articles and statements in links to advice from tax firms and the SEC.

That said, a traditional IPO generally doesn’t include warrants and a later merger with a right to redeem — it’s just a straight equity purchase. The SPAC shareholder has a right to redeem that isn’t characteristic of a traditional IPO. So there are warrant-, redemption- and merger- related tax considerations. There also is the issue of interest on the trust fund held by the SPAC from the time of closing of the SPAC offering until the business combination.

We include in the bibliography/links section a link to the statement of the former Acting Chief Accountant and former Director of the Division of Corporation Finance of the SEC setting forth the SEC’s position that the SPAC warrants are to be treated (at least under some circumstances) as liabilities rather than equity for the SPAC’s financial reporting purposes. See https://www.sec.gov/news/public-statement/accounting-reporting-warrants-issued-spacs. Whether that affects tax treatment to the warrant holder I do not know.

A SPAC unit generally consists of a share of stock and a fraction of a warrant. Both the stock and warrant are listed and traded, so the SPAC unit holder can sell the warrant separate from the stock. A unit usually costs $10 at issuance. I have not researched how much of that is allocated to equity versus the warrant for tax purposes.

If the SPAC target is a foreign company, the usual PFIC issues apply. There’s an article I wrote on PFICs on the Solari site.

Holland & Knight has published an article on taxation of SPACs (see https://www.hklaw.com/-/media/files/events/2021/06/spac-tax-presentation.pdf), but most of the considerations are relevant to the SPAC and the target business entities, not to the holder of units, stock or warrants.

There are no special IRS rules on taxing holders of SPAC shares, in particular, that I can find. I don’t know what you mean by “tax size” in your question.