By Jason Worth

Martin Ford’s book, Rise of the Robots, was not the book that I thought it would be. With its Isaac Asimov-sounding title, I thought it would discuss cutting-edge new robots designs; describe how they’re doing things even faster and cheaper; and make clear just how many more American jobs are imperiled. I figured I would be entertained at the cool new things robots are doing, while at the same time worried about future employment opportunities for human workers. Although there certainly are elements of the above in Martin Ford’s book, I found something much different. And what I found, in many ways, was even more worrisome.

Ford’s book reads more like an analysis of America’s labor and employment trends since World War II. Based on its content and subject matter, it would be more appropriate in an economics course than in engineering or computer science. In place of discussions of robotic developments and their human-like capabilities, there is instead much more discussion of labor force participation rates, worker productivity trends and offshoring of jobs. The book contains numerous charts from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics and Federal Reserve Bank, none of which I would have expected from a book entitled Rise of the Robots.

It would be fair to say that the subtitle of Ford’s book, Technology and the Threat of a Jobless Future, is a much better signal as to what the book is about. But as I read it, I thought an even more apt subtitle could have been: The Systematic Destruction of Jobs and the Middle Class in America, Since World War II. To explain why I say this, and to summarize Ford’s excellent book, I’m going to have to get into some economic analyses, including charts.

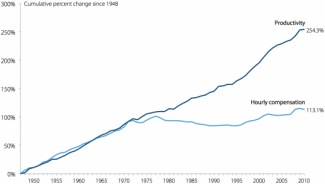

Economists often say that as laborers become more efficient, either through the use of better technology or better work processes, laborers are rewarded with increased wages. The graph below shows that this was the case in America from 1948 to 1973, where a direct correlation between improvements in labor productivity resulted in increased wages for workers. But an unfortunate thing happened around 1973. Although productivity continued to improve steadily to the present day, workers no longer shared financially from those improvements.

Growth of Real Hourly Compensation for Production and Nonsupervisory Workers Versus Productivity (1948–2011)

click on the image for a larger version

Source: Lawrence Mishel, Economic Policy Institute, based on an analysis of unpublished total economy data from the Bureau of Labor Statistics, the Labor Productivity and Costs program, and the Bureau of Economic Analysis’ National Income and Product Accounts public data series.

http://www.epi.org/publication/ib330-productivity-vs-compensation/

In fact, adjusted for inflation, the typical worker in America (working in a non-supervisory production capacity, in the private sector) earned 13% less in 2013 than he or she earned in 1973 (based on an adjusted weekly earnings of $767 in 1973 versus $664 in 2013.) In other words, American workers have been mired in a phase of stagnant wages since the early 1970s, despite the fact that their productivity output has been steadily improving all throughout.

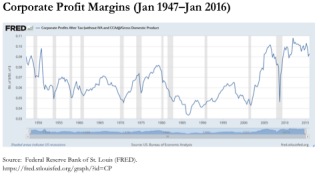

Corporate executives and their shareholders, since the early 1970s, have been taking the increased profits from improving productivity. And, as illustrated in the chart below, US corporate profits are near their all-time high.

click on the image for a larger version

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?id=CP

The shaded areas in the chart represent US recessions. Corporate profits sometime decline heading into, but certainly during, these shaded periods of economic contraction. But corporate profits often spring back rapidly after the recessions end. Ford asserts that this dramatic increase in profits post-recession is due not only to the resumption of normal economic demand, but is also due to the fact that corporations do not hire back workers after the recession is over to the same degree that they laid them off during the recession. In other words, corporations lay off workers quickly during the bad times, but hire fewer of them back (and more slowly) upon resumption of good times. Companies are able to do this because of productivity gains that are constantly occurring with the development and application of technology and better processes.

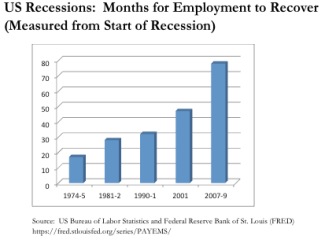

Evidence of this “quick to fire, but slow to rehire” trend is illustrated by the amount of time that it takes for the labor force to return to pre-recession employment levels. As illustrated in the chart below, which looks at the five most recent US recessions, it is taking longer and longer after each economic downturn before the same number of workers are employed as were working when the recession started. Where it took 17 months before the number of workers reached pre-recession levels after the 1974-1975 recession, it has taken 78 months before the same number of workers were employed as before the “Great Recession” of 2007-2009. Each recession is taking progressively more time to rebound, from a labor perspective.

click on the image for a larger version

Source: US Bureau of Labor Statistics and Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PAYEMS/

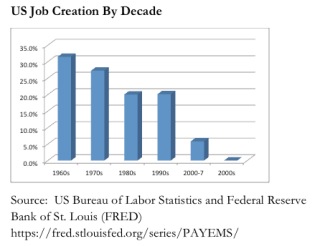

Because of improvements in productivity, US corporations have been creating jobs at an increasingly slower pace since World War II. In fact, with only one minor exception, every decade since World War II has created jobs at an even slower rate than the decade before it. The situation has become so extreme that during the decade 2000-2010, no net new jobs were created during that entire 10-year period. In fact, we ended that decade on December 31, 2009, with approximately 1 million fewer laborers working than were working on January 1, 2000. The Great Recession of 2007-2009 certainly resulted in a tremendous loss of jobs. But even if you were to measure the period just up to the start of that recession, from 2000 to 2007, our nation was still on track to have the worst decade of job creation in its post-war period (with a growth of only 5.8% at that time.) Another important thing to consider is that our economy needs to add approximately 75,000 to 150,000 per month, just to tread water, since that is the approximate growth in population from births and immigration. So, ending the 2000-2009 decade with no jobs created essentially means that an incremental 9 million people, at least, were unemployed than at the beginning of that decade.

click on the image for a larger version

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/PAYEMS/

Faced with a situation where jobs are not growing fast enough to even keep pace with population growth, and since it is taking longer after each recession before the workforce is back to pre-recession working levels, it is not surprising that people are leaving the workforce. As the next chart shows, labor force participation increased dramatically from 1970 to the 1990s (due largely to women either choosing to or needing to enter the workforce), peaked in early 2000, and has been declining rapidly ever since. The decline since 2000 represents the frustrated response from workers not able to get jobs, and they just give up looking and drop out of the labor markets altogether. Of course, this time period (2000 to the present) coincides with a dramatic upsurge in applications for food stamps, Social Security disability and numerous other forms of government assistance.

Labor Force Participation Rate (Jan 1948–July 2015)

click on the image for a larger version

Source: Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED)

https://fred.stlouisfed.org/graph/?id=CIVPART

The troubling outgrowth of all of these trends is a very large and ever growing divide between the rich and everyone else since the 1970s. Between 1993 and 2010, over half of the increase in US national income went to households in the Top 1 percent of income distribution. And this inequality has gotten even worse since then. An economist at the University of California, Berkeley, documented that 95% of total income gains during the years 2009 to 2012 went to the wealthiest 1 percent. This income inequality appears to be worsening, rapidly. Furthermore, US income inequality, as measured by the Central Intelligence Agency, is now on par with the Philippines; and the US ranks behind countries like Egypt, Yemen and Tunisia in this economic measure. The American Dream, whereby anyone can achieve a good life and rise up the ranks through hard work, appears to be essentially dead.

Even if you try do everything in your power to buck these negative employment trends, and in America that means getting a four-year college degree (especially in engineering or science), you still may not be successful at getting a decent paying job. According to one analysis, incomes for young workers with only a bachelor’s degree declined nearly 15 percent between 2000 and 2010, and the plunge began well before the 2008 financial crisis. And by some accounts, half of new graduates are unable to find jobs that utilize their education. And getting this degree is not cheap. College costs have soared 538 percent from 1985 to 2013, much of that cost being funded through student loans. 70 percent of US college students borrow, and the average debt puts students in a $30,000 hole before they even start their career.

Another problem in our current jobs environment is that, as documented by economists, the jobs most likely to permanently disappear during US recessions are the good quality, middle-class jobs (5 million of which vaporized from December 2007 to August 2013), but the jobs that tend to be created are low-paying, part-time jobs (3 million of which were created during that time.) Part of the reason that it is more likely that lower-paying jobs become available now is that companies have used information technology and automation processes to de-skill and make routine jobs that historically required more education, intelligence and creativity.

Because of globalization of business and improvements in cross-country communications (i.e. the Internet), it has been possible since the 1990s to send service sector jobs of all kinds “offshore.” We were sending manufacturing jobs offshore long before that, but the more complicated customer service and technology jobs started migrating in earnest in the 1990s. Much has been written about offshoring, so I probably don’t need to go into it that much here in this review. But, what Martin Ford discusses about offshoring that I think is very worthy of consideration is that the process is often a stepping stone to full automation. So, consider the various customer phone support, back office paper-pushing, computer coding and other value-added but “automatable” functions that can be simplified enough, with computer assistance, to be shipped to low wage service centers in India, China and other developing nations. These processes still required a human as part of the service delivery, although frequently these workers are just reading from a computer-generated script. Now, imagine that improvements in artificial intelligence, voice recognition and speech, on-the-fly language translation, machine-based programming and other technology developments have progressed to the point where these jobs can now be done entirely by computers. This is happening. And although millions of workers in India, China and other developing nations have quickly come into these jobs as a result of them being offshored from the US and Europe, they are very much at risk of losing them equally quickly. One example that supports this (although it’s a manufacturing example) is Foxconn, which makes the bulk of Apple’s consumer products like the iPad and iPhone. In 2012, Foxconn announced that it had plans to install up to one million robots in its factories. And already, between 1995 and 2002, China had lost about 15 percent of its manufacturing jobs. (I’m not sure why the statistic in the book ended at 2002, but I believe this downward trend has continued since then.) They are going to even lower-wage countries, like Vietnam, or being lost altogether to robots.

So, let’s just pause here for a moment and think about what we’ve just covered. The economic headwinds have been very much against the US worker since the early 1970s. His or her wages have been largely stagnant since then (after taking inflation into account.) Job creation has been occurring at slower and slower rates. As companies use computers and business processes to automate their businesses, the role of the human worker is becoming increasingly marginalized, and therefore lower-paying. And, even those jobs that grew rapidly overseas at the expense of US and European workers, are now in jeopardy of disappearing because of the same profit-oriented trends toward greater efficiency through automation. Pretty bleak picture!

When Americans lost jobs in the manufacturing sector several decades ago, economists said this was okay, because Americans would be “freed up” to pursue higher-paying jobs in the service sector. But those service sector jobs have been increasingly offshored or fully automated. Perhaps this means Americans should be “freed up” again to focus on the even higher-value-added service or knowledge based jobs. But, as computers get smarter and more capable, particularly through the application of artificial intelligence, there appears to be very few knowledge-based jobs left that will be immune to computerized job erosion. For example, one of the hardest professions you might think to be automated is that of the doctor or pharmacist. But the Jeopardy! game show winning AI machine from IBM, called Watson, has been tasked to understand and automate the health care delivery industry. Some futurists believe that the role of a doctor in the future could be dumbed-down sufficiently to the point where they enter pertinent information about their patients into a computer, like Watson, which accesses gazillabytes worth of clinical and other medical data to diagnose and prescribe the appropriate treatment to the doctor for execution. The same thing is currently happening with pharmacists, where computers are being deployed to double check for potential drug-interactions; and radiologists, whose job of looking at x-rays and making medical determinations are in the early stages of being replicated consistently by AI-programmed computers. If the role of these medical professionals, each representing highly specialized fields which requires years of extensive training and advanced schooling, can be automated, what profession is safe?

The machine assault against the modern worker is threatening virtually every profession. Journalists are at risk as computers can now reliably write news and sports articles. Musicians and artists are at risk as computers can now write beautiful music scores and compose works of art. Teachers and graduate students are at risk as machines can now reliably grade high-school and college essay papers (not to mention the easy multiple choice exams.) Delivery and taxi drivers are increasingly at risk. Amazon is experimenting with having drones fly packages to your house or place of business. As many as a quarter million taxi jobs may be destroyed by Uber and Lyft, once they convince even more governments to allow self-driving cars on the road. Hundreds of thousands of 18-wheeler delivery truck drivers will not be far behind. And even entry-level fast food workers are at risk now that the first gourmet hamburger making machine has débuted. (By the way, that machine will allegedly pay for itself within one year. It is no surprise that companies like Wendy’s are aggressively automating in response to the requirement by progressive cities like Los Angeles, San Francisco and Seattle for fast food chains to phase-in a salary increase to $15 per hour for fast food workers.)

As you might expect, the book concludes with a recommendation for how societies might attempt to cope with these trends; and there don’t seem to be many options. Limiting the growth and adoption of technology in the workplace does not seem practical. Wendy’s use of computerized hamburger making machines show how government salary mandates can easily be skirted, when all you need to do is eliminate the human from the supply chain. And, if the globalized workplace is viewed as a battlefield, the United States must continue to automate simply because our competitors are doing it; and we can’t let them have an advantage over us.

Instead, Ford makes a somewhat apologetic but well-reasoned argument in favor of a government-provided Basic Income or Guaranteed Income. Under this program, every citizen, regardless of income or need (although a means test could be implemented to reduce the program’s cost), would receive a monthly stipend sufficient to pay his or her basic living and food costs. Unlike current programs, such as Social Security, nothing would prevent recipients from having other sources of income, so there would be no disincentives to work.

Although I was philosophically opposed to the concept of a “socialist” type payment like this before reading Ford’s book, I’m more inclined to consider it now. For one thing, ongoing developments in the labor markets have increasingly forced millions of workers to seek various forms of government assistance such as food stamps, housing assistance and social security disability. So, you could argue that we’re already paying a form of basic income, just through a myriad of complex and overlapping local, state and federal assistance programs. Plus, governments could achieve a tremendous amount of administrative cost savings by rolling all of the existing assistance programs, including Social Security, into it. It would no longer be necessary to apply for and show compliance with all of these programs. Everyone gets a check; end of story. And all of the compliance and enforcement actions, including punishments for abuse, can go by the wayside. Such a guaranteed income could have benefits to society far beyond just enabling the needy to get by, which makes its potential adoption even more interesting. It could, potentially, reduce the crime rate, enable more people to move from urban to rural locations (stimulating growth in former ghost towns), free citizens up to pursue interests in the arts and other lower-paying professions, and enable more working mothers to stay home and raise their children.

But, something must give. In light of the stagnant wages workers have received since the 1970s, it is easy to understand how much of the economic growth since the 1980s has been fueled by increasing consumer debt levels. But skyrocketing bankruptcy rates and the Great Recession of 2007-2009 show that this model can’t continue. As robots and technology succeed in throwing even more workers out of factories and places of business, and the middle class gets increasingly further decimated, how will consumer spending, which accounts for approximately two-thirds of US economic activity, possibly continue to grow? At least it is possible to see some level of sustained consumer spending as a result of some form of Basic Income-type payments to citizens.

It’s hard to believe that a book so bleak could end with a silver lining. It’s even harder to believe the silver lining that got me hopeful was something that, before I read the book, I considered to be a socialist payment designed to ensnare all of a country’s citizens into reliance upon government largesse. I don’t know. This is one of those books that causes you to continue thinking about it long after you put it down, which is what I’m doing. But I can certainly say that I think I see the world a lot more clearly now that I’ve read it, even if I don’t like what I see.

Related Reading:

Book Review:

Our Final Invention: Artificial Intelligence and the End of the Human Era