“Words and language are the means by which we share our understanding of the world around us. The first signs of tyranny are when words lose their truth and are used merely as instruments of power and manipulation.”

~ Michelle Stiles

By Elze van Hamelen

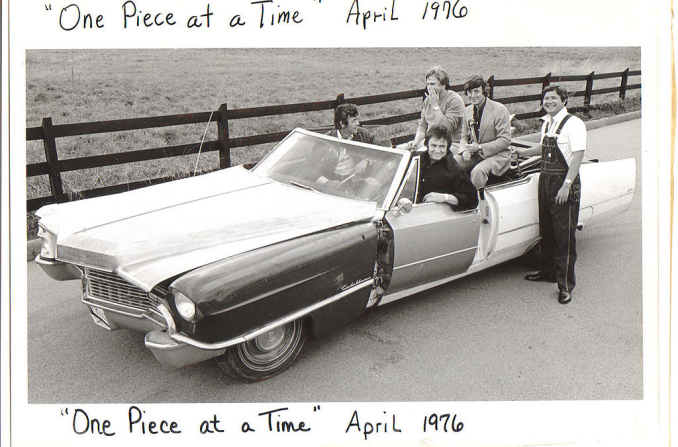

How is it that so many educated, intelligent people fall for propaganda? Why is it virtually impossible to engage in meaningful debate with those who get their news exclusively from the mass media? With the history that author Michelle Stiles describes in her book One Idea to Rule Them All: Reverse Engineering American Propaganda—which looks at more than one hundred years of propaganda—you slowly get an answer to those questions.

As a physical therapist who supports people recovering from knee replacement surgery, Stiles is not the person you initially would expect to write about propaganda and its historical roots. However, had she pursued an academic career in a related field, she probably would not have been able to adopt such a broad and in-depth perspective. In addition to considering the history of propaganda, she reflects deeply on Western culture and the Christian values on which it is based, describing how language gradually has been modified to make materialistic and collectivist values seem like the highest good. Change, of course, is partially a natural process, but the advent of mass propaganda makes it possible, to a great extent, to manipulate the values that a culture is based on.

Citing scholar Josef Pieper’s work, Abuse of Language—Abuse of Power, Stiles elucidates the pivotal distinction between true communication and propaganda. The two elements of authentic communication are that it is directed at another human being and is trying to convey truth about reality. In contrast, propaganda’s abusive messaging is not about conveying truth; its aim is to steer a person toward one or more desired behaviors. The relationship is one of control, not interaction. If we view authentic communication as a creative process, involving the sharing and expansion of the culture and values on which reality depends, it makes sense that when words no longer need to convey truth, eventually the social fabric and culture will start to unravel.

Stiles writes, “Those of us seeking to truly understand what we are up against and to be equipped for battle must deep dive into the action of words upon society, their correspondence with reality, the search for truth, and how they have been systematically corrupted and weaponized against Western culture and humanity in general.” She notes how changes in wording and the meanings of words contribute to this corruption and weaponization; even seemingly small changes in wording can indicate a tectonic shift in culture.

As a revealing example, Stiles explains how Darwinism altered the study of man. Before Darwinism, people were considered to be a creation of God, but the theory of evolution situated the study of man within the social sciences, taking God out of the equation. In the process, social scientists started replacing the notion of virtues and vices with more “neutral” descriptors of human characteristics. Virtue itself gave way to “pro-social behavior,” while vices like impatience and gluttony changed to “low frustration tolerance” and “the idea that obesity is genetically predetermined instead of under personal self-control.” An interesting example from the Netherlands comes from the shift in language to enumerate the number of people living in Dutch villages and cities; in the mid-19th century, we counted “souls,” but at some point, this changed to “inhabitants.”

When I was young, we used different pronouns for informal and formal situations in the Dutch language. In English, the pronoun would be “you” in both cases, but in Dutch, “je” or “jij” (German “du”) would signal a personal or close and informal relationship. (The English-language equivalent might be being on a first-name basis with someone.) The pronoun “U” (German “Sie”) is the formal “you,” signifying distance but also respect for seniority and achievement based on merit. As a student, I found it confusing that some professors insisted that we address them as “je/jij,” while others were offended if we did so (and vice versa). Removing this distinction between the formal and informal, as is increasingly happening in both business and educational settings, works as a great “equalizer”—the shift in values is from one of personal relationship and individual characteristics to collectivist values. It is no surprise, then, that pronouns are changing yet again, this time to support gender confusion and wipe out the notion of biology-based difference between the sexes.

And what to make of other recent changes in wording and word meanings? “Meat” is no longer meat; it is “protein.” But proteins can be insect-, lab-, or plant-derived, too—so, why not take the animal out of the equation altogether?! Or consider the words “freedom” and “democracy,” still in use, but for some, with meanings that have been changed, as in “We need to forbid the subversive activities of this opposition political party and we need to censor non-state-sanctioned information to protect democracy.” Or how about, “Freedom means having the freedom to choose to be injected with an experimental gene technology as a condition to participate in society and keep your job.”

That the history of propaganda goes back more than one hundred years in supposedly “free” societies gives pause. Propaganda campaigns are not just little lies and manipulations to sell people government policies or consumer products; propaganda actively undermines the values on which culture is based. To illustrate these sobering facts, Stiles begins her story in the early 20th century in the middle of World War I. President Woodrow Wilson won his second term in 1916 with the slogan “He kept us out of war,” and among the lower and middle classes, there was no support for U.S. participation in the conflict in Europe, which they saw as a businessmen’s war. To get the public on board for participating in the war, Wilson’s administration established an impressive propaganda apparatus, operating out of the Committee on Public Information (CPI).

The means employed to persuade the common man about the merits of the war were large-scale and far-reaching:

- Distinct departments were responsible for: 24-hour-a-day news releases (ranging from messages for the press to human interest stories for magazines to bulletins for officials); advertisements and billboards; “visual publicity” (working with artists, illustrators, cartoonists, and designers); and film scripts for Hollywood.

- The CPI also enlisted academics to write pamphlets.

- A speakers’ bureau of so-called “Four Minute Men” (both local leaders and promising schoolchildren) were trained to give short persuasive speeches advocating for the war. The committee also had access to a speakers’ list of 10,000 prominent citizens.

- The CPI provided schools and teachers with materials for classroom discussions.

Ominously, speakers were encouraged to keep an eye on who was against the war—and to report them. Congress passed the Espionage Act in 1917 to make it possible to prosecute troublesome critics. (This, not coincidentally, is the same law under which the U.S. is currently trying to prosecute journalist and whistleblower Julian Assange.) The Sedition Act of 1918 made criticism of the incumbent administration illegal.

The entire CPI operation—the most expensive in history up to that time—was enormously successful. “It proved that public opinion could be created,” writes Stiles. “Debate was no longer necessary. The citizen was now a consumer, to whom the ‘truth’ was sold by opinion makers in marketing campaigns.” Given this success, it should come as no surprise that propaganda didn’t stop with the CPI. On the contrary, the war propaganda campaign kicked off the further development of techniques and operations to influence the public. The 1898 book by Gustave Le Bon titled The Psychology of the Masses greatly influenced the propagandists with its argument that the masses are not moved by logic but by emotions and images. As Stiles summarizes, “From this point of view, ideas need no longer needed to be explained, argued or debated.”

In her book’s subsequent chapters, Stiles shows how propaganda has grown from experimental campaigns to become a problem that affects and corrupts almost every facet of information creation and distribution, as well as the institutions involved. She shows that propaganda is not merely misleading information, or even lies, and it is not something of which only dictatorial or totalitarian regimes are guilty. Rather, it is an extremely sophisticated set of techniques that feed citizens, students, and consumers predetermined opinions, policies, and worldviews.

The power of propaganda, according to Stiles, lies in the fact that we have an implicit and natural trust in our information sources. We cannot personally verify or check all information, which is why we rely on shortcuts, such as trusting what “experts” tell us. Stiles points out that this worked in small communities, where our culture and use of language traditionally were inspired from the immediate environment. In today’s society, however, with its economies of scale, our sources of information are at a great remove; as a result, they no longer are easily or locally verifiable. “Modern propaganda focuses on all channels that we trust automatically and without reflection. With that, the discussion is decided before you even begin to think about it,” explains Stiles. “Much of that information is not factually based, but contributes to our beliefs about reality.” Tangible reality as we experience it here and now is no longer decisive; what is “real” is determined by Hollywood and television programs. The problem of people who seem to be “hypnotized,” says Stiles, is not that they can no longer think, but that their reality and core beliefs have been manipulated by sophisticated propaganda campaigns—well before they consciously started thinking about it.

Analyzing propaganda in Western societies is simultaneously a study in how power structures operate. Propaganda operations are extremely expensive, and only very wealthy parties such as the State, large multinationals, foundations, and UN agencies (and their NGO partners) can pay for them. This is not a level playing field. The average citizen and authentic bottom-up initiatives are in for a stiff fight when they try to share authentic dissent with larger audiences. In short, Stiles’s book is relevant not just to current propaganda but to power structures and the money flows around them.

What stands out when reading One Idea to Rule Them All is how relevant this history still is—and how important it is to know this history to understand our present historical moment properly. The accessibly written book is structured like a textbook; each chapter provides a clear explanation of a piece of history, which Stiles then summarizes in key points and concepts. In addition, Stiles has published a study guide with questions for reflection and materials for follow-up research. These are excellent resources to go through with high school or university students being taught very different values than those that someone with a Western-Christian cultural heritage grew up with. The concepts Stiles explores are widely applicable, even and especially for the delusion(s) of the day, and they may provide an opening to have conversations that reach beyond mass media soundbites.

Purchase the Book:

One Idea to Rule Them All: Reverse Engineering American Propaganda

Related Solari Report:

Soft Mind Control: More than 100 Years of Propaganda with Michelle Stiles

Read the book and well worth your time. It is an easy read, so I believe teenagers could benefit from this book also. No hiding behind grand abstractions starting with mass “whatever you fancy”. A clear cut road to your expression of individuality, even if you like to express that thru groups.