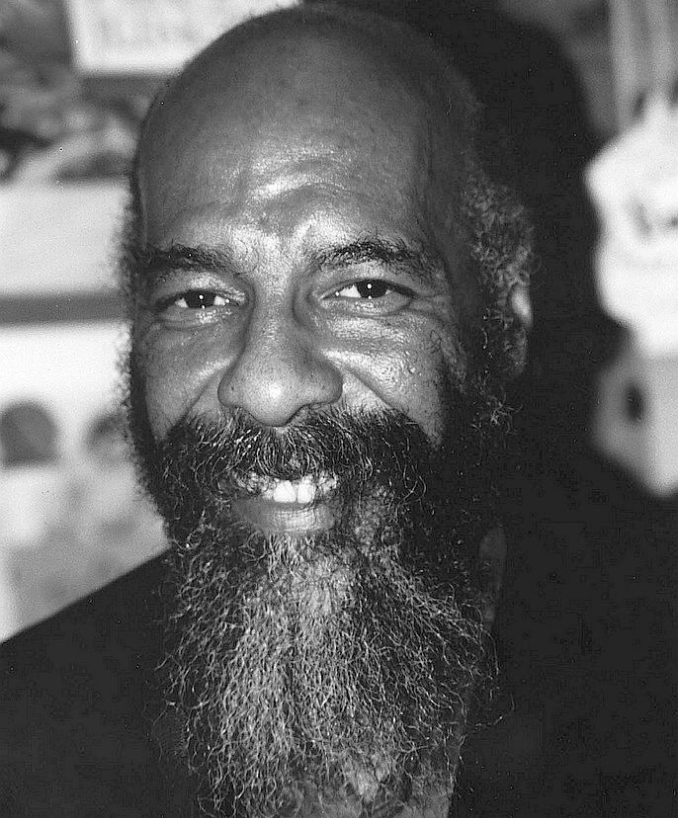

This week’s Hero is California homeowner George Sheetz, a litigant who in 2016 brought a case on a $24,000 municipal fee; the case was appealed to the Supreme Court. On April 12, 2024, the Supreme Court announced a unanimous ruling in favor of Sheetz. We recognize Sheetz for his contribution to legal precedent at the highest level (that is, preventing the taking of property by a local jurisdiction through the imposition of predatory statutory building permit fees unrelated to costs of the taxing jurisdiction).

The Supreme Court summarized the background of the case as follows:

“As a condition of receiving a residential building permit, petitioner George Sheetz was required by the County of El Dorado to pay a $23,420 traffic impact fee. The fee was part of a ‘General Plan’ enacted by the County’s Board of Supervisors to address increasing demand for public services spurred by new development. The fee amount was not based on the costs of traffic impacts specifically attributable to Sheetz’s particular project but rather was assessed according to a rate schedule that took into account the type of development and its location within the County. Sheetz paid the fee under protest and obtained the permit. He later sought relief in state court, claiming that conditioning the building permit on the payment of a traffic impact fee constituted an unlawful ‘exaction’ of money in violation of the Takings Clause [of the U.S. Constitution].”

Delivering the opinion of the Court, Justice Amy Coney Barrett noted:

“The California Court of Appeal rejected [Sheetz’s] argument because the traffic impact fee was imposed by legislation, and, according to the court, Nollan and Dolan [two similar cases in which the Supreme Court struck down a permit fee] apply only to permit conditions imposed on an ad hoc basis by administrators. That is incorrect. The Takings Clause does not distinguish between legislative and administrative permit conditions.”

As the Court further explained:

“The Court’s decisions in Nollan and Dolan address the potential abuse of the permitting process by setting out a two-part test modeled on the unconstitutional conditions doctrine…. First, permit conditions must have an ‘essential nexus’ to the government’s land-use interest, ensuring that the government is acting to further its stated purpose, not leveraging its permitting monopoly to exact private property without paying for it…. Second, permit conditions must have ‘rough proportionality’ to the development’s impact on the land-use interest and may not require a landowner to give up (or pay) more than is necessary to mitigate harms resulting from new development.”

Finally, the Court wrote:

“The County’s traffic impact fee was upheld below based on the view that the Nollan/Dolan test does not apply to monetary fees imposed by a legislature, but nothing in constitutional text, history, or precedent supports exempting legislatures from ordinary takings rules. The Constitution provides ‘no textual justification for saying that the existence or the scope of a State’s power to expropriate private property without just compensation varies according to the branch of government effecting the expropriation.’”

Related:

Sheetz v. County of El Dorado, California

Supreme Court Issues 9-0 Decision

The government had George Sheetz “over a barrel.” He took his case to the Supreme Court—and won.

These cases are super important. Wow – prescient, consequential and far reaching. This man’s name will always be remembered and cited.in the future. Can Solari start a category – called: “How to go Down in History” or “Spend a few hours a week on How to Be remembered: Leave your own Small, Local, National or Global Legacy”? 🙂