“Plague justified the rules that kept a person in her place. . . . We’ve seen how plague became the reason, just like terrorism today, for social regulation, for saying how children must behave, for taking a worker’s right to choose what work he wanted, for deciding which of the poor are worthy of help and which are just wastrels. Plague enforced frontiers that were otherwise wonderfully insecure, and made our movements and travels conditional. It helped to make the state a physical reality, and gave it ambitions.” ~ Michael Pye, The Edge of the World

By Catherine Austin Fitts

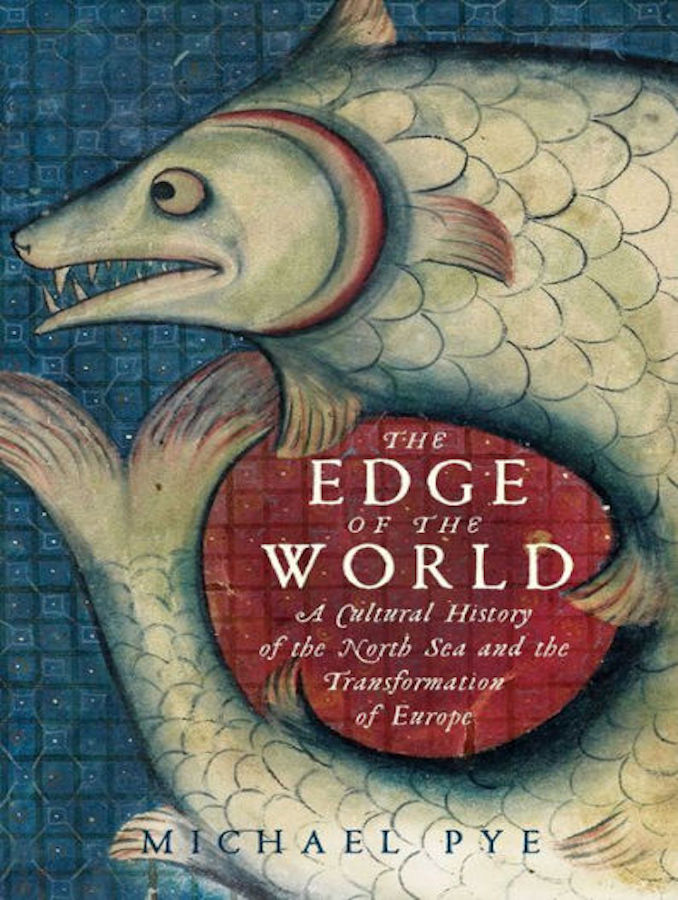

The Edge of the World: A Cultural History of the North Sea and the Transformation of Europe by journalist Michael Pye is a history of the people and cultures who traded across the North Sea and into the trade routes of Europe, the Middle East, and Asia during the Middle Ages. This included the Frisians, Dutch, Vikings, Danes, Finns, Germans, English, and Scots. The book was published in 2015 to accolades from establishment sources, including being declared one of the year’s 100 notable books by the New York Times. The Wall Street Journal described The Edge of the World as “beautifully written and thoroughly researched.”

I purchased The Edge of the World along with a large selection of books about the Frisian people, the Hanseatic League, and the business history of the Dutch. What were the economic and trade models that built this area of the world? Why were the Frisians so astute at creating and managing currencies? How was the Hanseatic League formed, and what were the reasons for its success? Why did it diminish as nation-states developed?

Pye dives into many fascinating threads of economic and cultural development from the time of Charlemagne onward: the development of books, education, and literacy; how settlements were created and trade conducted; the writing of the law; fashion and morals; currency and money; science; and how love, sex, and marriage were conducted. Pye’s rich details and stories create a fascinating look into numerous civilizations as they developed along the North Sea. This was a complex world of many cultures.

Throughout this history, we see a continual see-saw between trade and war. Which is more profitable—pillaging a people or trading with them? It is easy to understand the constant arrangement of intermarriage to create connections that could cut down on the violence. I am reminded of Jack Ma’s recent comment, “When trade stops, war starts.” There is no doubt that the perpetual pillaging made for a brutal existence.

The next-to-last chapter in The Edge of the World is about “The Plague Laws,” beginning with the Black Death in the 1300s. Pye writes, “This medieval horror had very long consequences. It is the start of the process we still know of anxious, insistent social controls, of policing lives; and what goes with it, an official suspicion of the poor and the workless, who are never just unfortunate. Our nightmares begin with their nightmares, in the 1340s.” It turns out that plagues helped fuel the rise of a centralized nation-state, and with it the centralized control of labor and taxation, and the concentration of cash flows and capital.

In his final chapter, Pye rejoices in the great cities and civilizations this theft of intellectual capital, markets, trade, and freedom created. He says, “In Antwerp all this produced a glittering civilization which spawned so many of our attitudes: To art, insurance, shares, genius, power as a great show: to the possibility of engineering the world as we want it. When war broke up Flanders, when the northern provinces broke away, those attitudes came to Amsterdam.”

Having thoroughly enjoyed Pye’s early insights on the Frisian culture and the development of the Hanseatic League, the book’s abrupt ending and Pye’s conclusions in favor of centralization left me in a state of shock. When the Covid-19 pandemic began, Jon Rappoport referred to it as the latest development in a 10,000-year-old war. Reading The Edge of the World: A Cultural History of the North Sea and the Transformation of Europe underscores how true this is.

One wonders if the folks at the Harvard Corporation and Rockefeller and Gates Foundations and the leadership gathering annually at the Bohemian Grove—or the hordes of academics they fund through the Council on Foreign Relations and intelligence agencies—read Pye’s book. One also wonders whether the accolades the book received depended on the author’s support for forced labor, tyranny, and the concentration of capital. Whatever the truth of the matter, we are dealing with a very old playbook. We can thank Pye for his astounding demonstration of that fact. What is the old saying? “The proof is in the pudding.”

Purchase here:

Interesting footnote: As part of his effort to “unify” (that is, exert control) over Europe, Charlemagne standardized what we now call Gregorian Chant as well as the text of the church liturgy, replacing local sacred music traditions with “Roman chant.” Maybe it’s a stretch, but the dominance or influence of American “popular” music along with American “culture” in general over most of the world seems similar.

Are you planning on researching more on these plague laws? It’s a very interesting topic.

It is on my list. Would be much better to find someone doing it if I can.

I received this book yesterday. I am just one chapter in, and totally captivated. Healing water, Medicine “middlemen”, and human trafficking…

It is an extremely interesting phenomenon that “elites” from time to time speak openly and bluntly about their doings in the world. I think it reflects confliction, and the desire to somehow retain a shred of dignity in spite of doing deeds that frequently are unspeakably horrific.

Dying in such a state is something I fear above all else.